The Missing Avengers

By John Flores, Editor of Redwood

6 minute read

The Avengers “Infinity War” saga has been seen by millions of people worldwide. The films shattered viewership records as Endgame, the finale, surpassed Infinity War to become the highest grossing movie of all time. The Avengers’ success has led to numerous comparisons to the beloved Star Wars franchise, as commentators predict the production of many more Avengers films to come.

Like Star Wars, the Marvel-Avengers universe has been criticized for its exclusion of people of color. Who can forget that Star Wars (1977) depicted a futuristic world without any people of African descent. Marvel is aware of these criticisms and seemingly tried to produce a more inclusive series, and they had an incredibly large cast to draw from. Endgame alone featured more than fifty Marvel characters including a number of Marvel’s Black heroes, such as the Black Panther, T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman); War Machine, James Rhodes (Don Cheadle); Falcon, Sam Wilson (Anthony Mackie); and a briefer but notable role for Valkyrie, Brunhilde (Tessa Thompson), among others.

Endgame, in fact, surprised many of us when it stuck to the comic-book arc in which Sam Wilson becomes the new Captain America and leader of the entire Avengers team. In one of the final scenes of the film, Steve Rogers (Chris Evans) decides he will retire and anoints Wilson as his successor, entrusting him with his iconic red-white-and-blue vibranium shield. In this same vein, the most Nordic-looking Avenger, Thor (Chris Hemsworth), decides to relinquish his hereditary right to rule over his homeland, Asgard, and passes his privilege to Valkyrie who he asks to govern the kingdom in his stead.

I have been reading Marvel comics since I was a kid, and I enjoyed aspects of the Avengers. But as I watched Endgame, I couldn’t help but wonder: Why isn’t there even one Latinx Avenger?

To be sure, Zoe Saldana (of Puerto Rican and Dominican descent) stars in the films and plays a pivotal role in them. However, she does so not as a Latina but as an alien.

The media often depicts Latinos as “new immigrants” or as recent arrivals, but Spanish-speaking people have lived in what is today the United States since the colonial era (e.g., St. Augustine, Florida, was founded in 1565 and Santa Fe, New Mexico, circa 1610). About 150,000 Mexicans were forcefully incorporated into the expanding United States after the Mexican American War, and close to a million Puerto Ricans were pulled into the U.S. empire in the 1890s after the Spanish American War. In the aftermath of these wars, American corporations migrated into Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Nicaragua, and other Latin American countries. They extracted natural resources and established the transportation lines that began facilitating Latin American migration back into the United States. In 1917, the U.S. government formalized this early migration stream by creating a labor procurement program with Mexico, which recruited thousands of Mexican workers into the United States.

When the U.S. economy entered into a severe recession in 1921, Mexicans were now accused of stealing American jobs. They were denigrated as un-American aliens and targeted for deportation. A pattern emerged that continues to this day: Mexicans would be encouraged to migrate and work in the United States when the U.S. economy was expanding but would be scapegoated as aliens and expelled from the country when the economy was contracting. Treating Mexicans as deportable alien workers would have pernicious consequences for all Latinos. During subsequent crises in the 1930s, 1950s, 1970s, and in the years leading up to our present, if you looked like a Mexican, you could be defined as an alien and marked for expulsion. As a consequence of this history of “alienization,” while Latinos have lived and labored in the United States for generations, contributing to this country and enriching it in a wide-variety of ways, as a people, they remain incredibly unintegrated and underrepresented.

Evidently, Thanos did not have to snap any Latinos out of existence—Marvel did that for him. Hollywood has long contributed to the erasure of racial minorities, and it isn’t for lack of opportunity. The “Infinity Saga” includes a whopping twenty-three films, including Dr. Strange. In the comic, Dr. Stephen Strange is mentored by the Tibetan known as the Ancient One. Instead of hiring a Tibetan actor to play the Ancient One, Marvel decided to cast the British actress Tilda Swinton in this role. Defending this decision, director Scott Derrickson candidly explained, “The Ancient One in the comics is a very old American stereotype of what Eastern characters and people are like, and I felt very strongly that we need to avoid those stereotypes at all costs.” Apparently, Derrickson couldn’t conceive of a way of depicting a Tibeten character in a non-stereotypical way, and so he solved his own dilemma by re-casting the character as a white European.

This example underscores a broader pattern of racial exclusion: The Avengers films feature no Asian American heroes. While a Chinese national named only Wong (played by the actor Benjamin Wong) appears in Infinity War and Endgame, the series assigned the most screen time to the Korean and French-Russian actress, Pom Klementieff, who does not play an Asian superhero but an alien.

As with Latinos, Asian people have a long history of living, laboring, and enriching the United States, but they too have been defined as unassimilable aliens and snapped out of our historical memories. After the Mexican American War, the United States and other European powers “opened China” to foreign corporations by force through the Treaty of Tainjin (1851), the Burlingame Treaty (1868), and the “Open Door policy” (1899). As U.S. corporations captured new markets in Asia, Chinese workers followed these trade networks into the United States. Chinese laborers helped lay the transcontinental railroad and worked in incredibly dangerous tunneling and mining projects. Many lost their lives as they helped build critical infrastructure in California and the Pacific Northwest. By the late-nineteenth century, more than 100,000 Chinese lived in the state of California alone.

After the Spanish American War (1898), the United States occupied the Philippines. In High School, I was taught nothing of what the United States did in the Philippines, but in college I learned of the so-called “Philippine Insurrection.” In the U.S., what we call an insurrection usually involves a U.S. occupation. The U.S.-Phillipine War has been called our “First Vietnam” by progressive historians. More than 200,000 Filipinos died in a war for national liberation in opposition to the U.S. occupation. After the war, labor recruiters began prodding landless Filipinos to migrate to Hawaii to labor on plantations owned by U.S. firms. Filipinos soon began making their way to the continental United States.

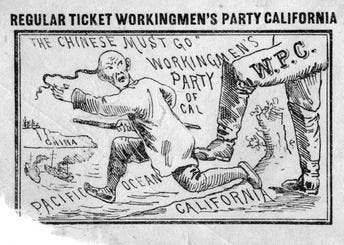

While U.S. companies continued to recruit exploitable (read: highly-profitable) Chinese and Filipino workers, labor competition engendered conflict in California, a dynamic exacerbated by the recession of 1873. Opportunistic and influential white Americans—bankers, merchants and journalists—now banded together with unemployed white workers around the cries, “California for Americans!” and “The Chinese Must Go!” They called for a wall to be built around the United States to stop Chinese migration, they torched Chinese neighborhoods, and through a series of violent pogroms, drove many Chinese away. The U.S. government facilitated this violent expulsion through a series of acts, including the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), which defined the Chinese as aliens unfit to become U.S. citizens and denied new Chinese workers the right to immigrate. By 1924, the U.S. government had established the “Asiatic Barred Zone,” restricting almost all Asian immigration, and the Supreme Court had ruled that Asians were not “white” and therefore ineligible for U.S. citizenship.

Latinx and Asian people have a little-known but interconnected history: Both have been racialized as unassimilable aliens, and while the Chinese people were the first to be barred from entering the United States, the Mexican people were the first to be deported on a grand scale.

The omission of Latinx and Asian people from our history and films serves to erase their present-day contributions to our economy and society. The Mexicans and Central Americans who harvest the food on our plates remain absent from any national discussion or Congressional hearing on American agricultural production. Likewise, Asian labor continues to enrich U.S. corporations. Apple, Nike, Hewlett Packard, and others all have low-wage operations in China, and Chinese workers have led massive labor struggles in the past few years that remain underreported in the United States. Mexican and Chinese workers remain out of sight and out of the American mind.

To be sure, representation is not equivalent to liberation. But in the tradition of Marvel’s What if…?series, what if we found not one, but several Latinx superheroes who could join the Avengers? Would their presence raise questions about immigration and family separation? Would these Avengers be Guatemalan, Chilean or Salvadoran and would we then talk about what the United States did in Guatemala in 1954, Chile in 1973, or El Salvador in the 1980s? Would an Asian American superhero compel us to recognize the incredible contribution of Asian labor in America, and would their presence lead to the inclusion of others? Would a Native American Avenger prompt us to talk about Standing Rock, land theft, and genocide? Films like the Avengers provide us with an opportunity to rethink our heroes and society but, unfortunately, Marvel continues to fall short. We need to find our missing Avengers. Our American saga remains incomplete without them.